The long-spined sea urchin Diadema antillarum is a keystone species. Coral reefs rely on healthy sea urchins to eat algae so coral can thrive. Healthy coral means healthy fish, and their positive impacts continue up the food chain.

In early 2022, long-spined sea urchins in St. Thomas began to quickly die in large numbers. Scientists rushed in to find the cause and have discovered that a microscopic parasite swarms the body and spines of the urchins, eating them alive.

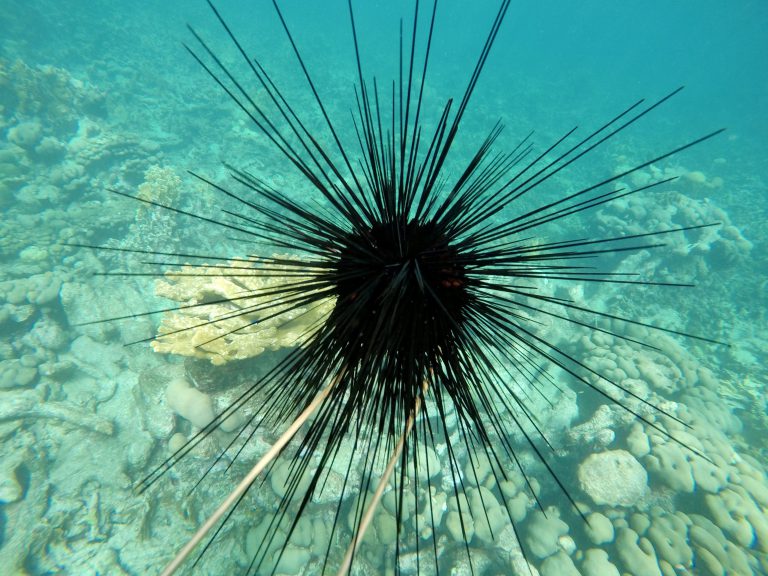

Diadema antillarum, also known as the long-spined sea urchin. Photo by UF/IFAS Don Behringer.

The culprit, a microscopic organism called a scuticociliate, appears most similar to Philaster apodigitiformis, a type of protozoan parasite. It began decimating sea urchin populations around the Caribbean, and within days of being symptomatic, urchins were dying. In a matter of months, losses were reported in nine more locations across the Caribbean, including off the Florida coast.

“The research team was still processing samples from the last site where a die-off occurred when we would get calls about a new location with dying urchins,” said Don Behringer, UF/IFAS professor of marine disease ecology and lead on a National Science Foundation RAPID grant that made the work possible. Behringer is also a member of the UF Emerging Pathogens Institute. “It only took a couple weeks for the majority of the long-spined urchins to be wiped out at a specific site. Rapid-response funding like this allows us to go to locations to sample and assess environmental conditions quickly and learn from it.”

Mass mortality events of this size can fundamentally change marine ecosystems for the worse. The most recent sea urchin die-offs were like those that occurred in 1983, when 98% of sea urchins were lost in 13 months. Researchers never discovered the cause of that die-off, which left many questions regarding protection of reefs from future events like it. Some coral reef systems never recovered and still feel the effects of those losses today nearly 40 years later. Some reports state that urchin populations at impacted reefs have only reached 12% of what they were before the 1980s mortality event.

“We had to act very fast. You really have to act within a week or two, or you’ll lose your chance,” said Ian Hewson, Cornell University marine ecology professor whose lab focuses on marine diseases. “These mass die-offs usually blow through extremely fast and sometimes if you get there too late, you’ll only be left with diseased animals and won’t even know what ‘normal’ looks like.”

Researchers identified the parasite relatively early on and validated their discovery through a series of experiments. They started with analyzing fluid from the urchins’ bodies, which is comparable to a blood sample, where they first discovered the parasite. From there, they isolated the pathogen and let it multiply. Then, they needed to confirm in a controlled setting that the identified pathogen was causing the deaths.

“We were really lucky to have access to urchins that were raised in a controlled environment and that we knew had not been exposed to the ciliate,” said Behringer.

Urchins are difficult to hand rear in aquaculture environments. UF/IFAS associate professor of restoration aquaculture Josh Patterson, in partnership with The Florida Aquarium, has learned how to hand rear the animals. His primary goal is to raise urchins for release into the wild to help restore coral reefs, but in this case, the healthy urchins helped validate the researchers findings out in the field.

“When this disease went through the Caribbean, it was impossible to know which urchins pulled out of water were exposed to the parasite,” said Patterson. “We had cultured urchins in tank that were naïve, known to be uninfected, that could help confirm what was causing the mass deaths of urchins in the wild.”

Those healthy urchins, raised in Patterson’s lab, were taken to the University of South Florida to be infected with the ciliate. Within four days, the previously healthy urchins were showing signs of illness, confirming the parasite to be the offender.

“Other parasites similar to this one are known to cause disease in other organisms but have not been implicated in urchin disease outbreaks, in the Caribbean or elsewhere,” said Behringer. “It appears to act in a micropredation mechanism where it swarms the urchins and starts multiplying and rapidly eating away at them.”

Photo by UF/IFAS Don Behringer.

Researchers are unsure why the parasite struck when it did or what caused it to be so voracious, but that is a question they hope to answer in the future. The information gained from this research has prompted further questions that will help scientists understand the parasite and the long-term effects of these die-offs on coral reefs.

And what about the die-offs in the ’80s? Could this parasite have been the culprit then, too?

Unfortunately, there are no remaining tissues or samples available from urchins impacted by the 1983 mass mortality event. Even though scientists have no way to compare this event to historical losses, the information gained from the 2022 event can help conserve populations in the future.

“We documented current algae coverage, urchin abundance and other species present before, during, and after the die-offs,” said Behringer. “We can use this information as a baseline from which we can compare a year, two years, five years, 10 years and beyond. It helps us create a clearer picture of the impact urchin loss has on the condition of the reefs and the broader reef community. We’re fortunate we had the opportunity to collect the data we did.”

As of December 2022, it seemed that the die-offs had stopped. In some areas, new urchins were being reported, a good sign of recovery. However, just recently, new reports of dying urchins have come in from the Cayman Islands and U.S. Virgin Islands.

“We cannot say for sure if it is the return of the same parasite, but it appears ominous,” said Behringer.

“The previous die-off was extremely consequential for the reefs that were impacted and some never recovered,” said Behringer. “This time we know the culprit and are trying to figure out how and why it emerged.”

This project would not have been possible without the support of many, including the funding agencies, the National Science Foundation, Florida Sea Grant, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. Special thanks to the project partners including the University of South Florida, University of the Virgin Islands, Virgin Islands Government and many more.

About UF/IFAS

The mission of the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) is to develop knowledge relevant to agricultural, human and natural resources and to make that knowledge available to sustain and enhance the quality of human life. With more than a dozen research facilities, 67 county Extension offices, and award-winning students and faculty in the UF College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, UF/IFAS brings science-based solutions to the state’s agricultural and natural resources industries, and all Florida residents. ifas.ufl.edu | @UF_IFAS

About Florida Sea Grant

Hosted at the University of Florida (UF), the Florida Sea Grant College Program supports research, education and Extension to enhance coastal resources and economic opportunities through a partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the State University System of Florida, and UF/IFAS Extension in counties statewide. flseagrant.org | @FloridaSeaGrant

Media Contact

Tory Moore is a public relations specialist with UF/IFAS Communications. For more information on this story, please email torymoore@ufl.edu.