October brings scares, frights, and mysteries, and alongside Halloween, it’s also National Seafood Month. We’re shining a light on a serious—and unsettling—issue in the seafood industry: seafood fraud. Discover how former Aylesworth student Samuel Kwawukume and researchers at Florida State University (FSU) have worked to promote transparency in the seafood industry.

Many people might assume that an establishment on a beach, adorned with boat-themed decor, fishing nets, and a maritime menu serves locally sourced seafood. However, this is not always the case.

Many people might assume that an establishment on a beach, adorned with boat-themed decor, fishing nets, and a maritime menu serves locally sourced seafood. However, this is not always the case.

“People flock to coastal businesses for fresh and locally sourced products, but this can be misleading,” says David Williams, president of SeaD Consulting. “Customers often do not receive the locally caught seafood they expect.”

This is known as seafood fraud, which involves receiving different species than requested or seafood sourced internationally instead of locally. It has become a nationwide challenge, affecting nearly every level of the supply chain, including restaurants, festivals, vendors, retailers, and even some wholesalers and distributors.

Samuel Kwawukume, a recent graduate of Florida State University with a master’s degree in nutrition and food science, was at the forefront of addressing issues in seafood fraud.

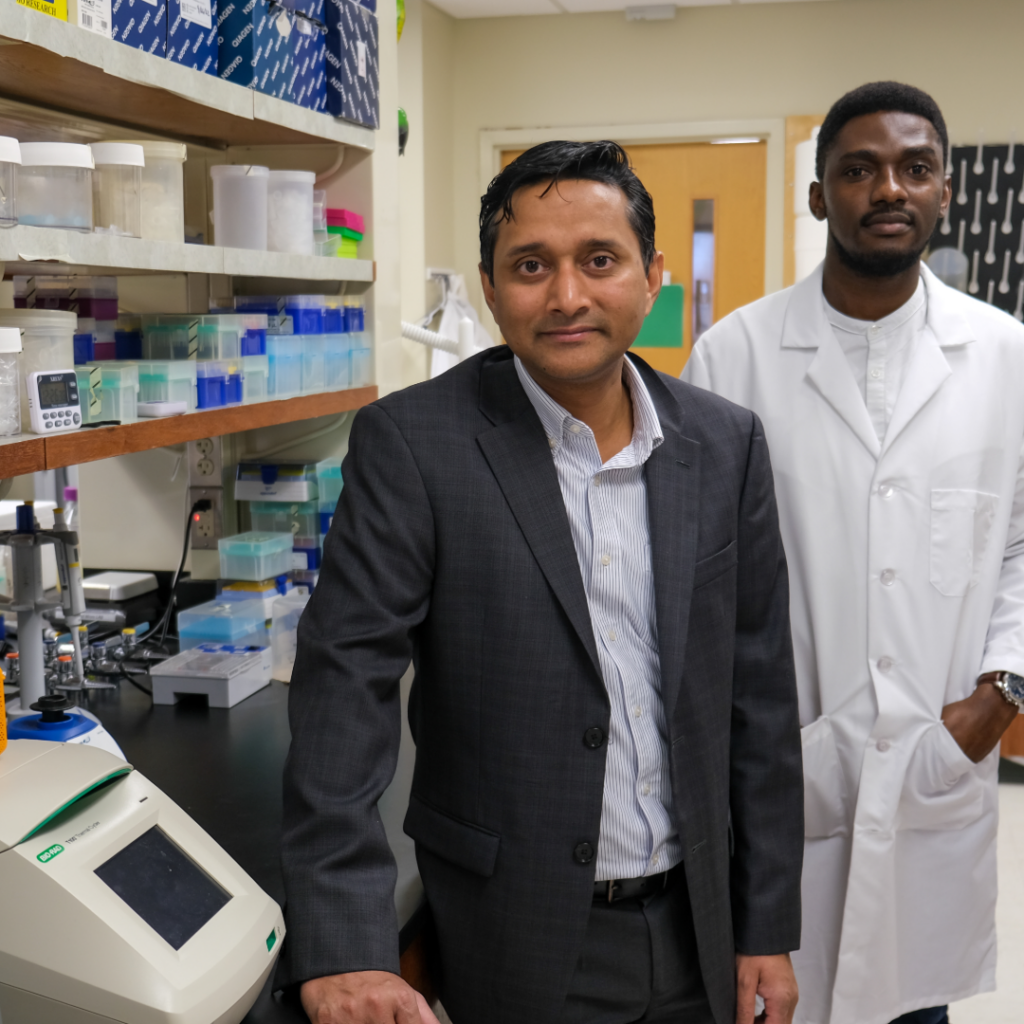

In 2023, he received the Florida Sea Grant Aylesworth scholarship, which funded his research on seafood species identification in Associate Professor Prashant Singh’s lab. At FSU, Samuel and the research team developed a rapid test known as PCR lateral flow assays to identify seafood species. The test utilizes molecular techniques to analyze DNA from shrimp tissue and determine the identity of samples.

“Studies from NGOs like Oceana show an average of 30% mislabeling, with species like red snapper, tuna, and shrimp being highly susceptible, while species like red snapper can be as high as 73-100%,” says Kwawukume. “The lab’s mission is to ensure the safety of seafood distributed nationwide. Several risks are associated with mislabeled seafood, including foodborne illnesses and economic fraud, which is hurting the U.S. coastal communities.”

Innovations in Seafood Identification Technology

Associate Professor Prashant Singh with former graduate student researcher and Aylesworth Scholar, Samuel Kwawajume. Photo by Melissa Powell, Florida State University.

Before the recent test design, industry professionals used FDA-approved DNA barcoding and real-time PCR assays for seafood identification, which involved overnight shipping of samples to an external food testing lab.

“The standard DNA barcoding method is expensive and can cost between $100-200 per sample. Additionally, it is time-consuming, taking up to three to five days for results and requiring skilled personnel and costly equipment,” says Dr. Singh.

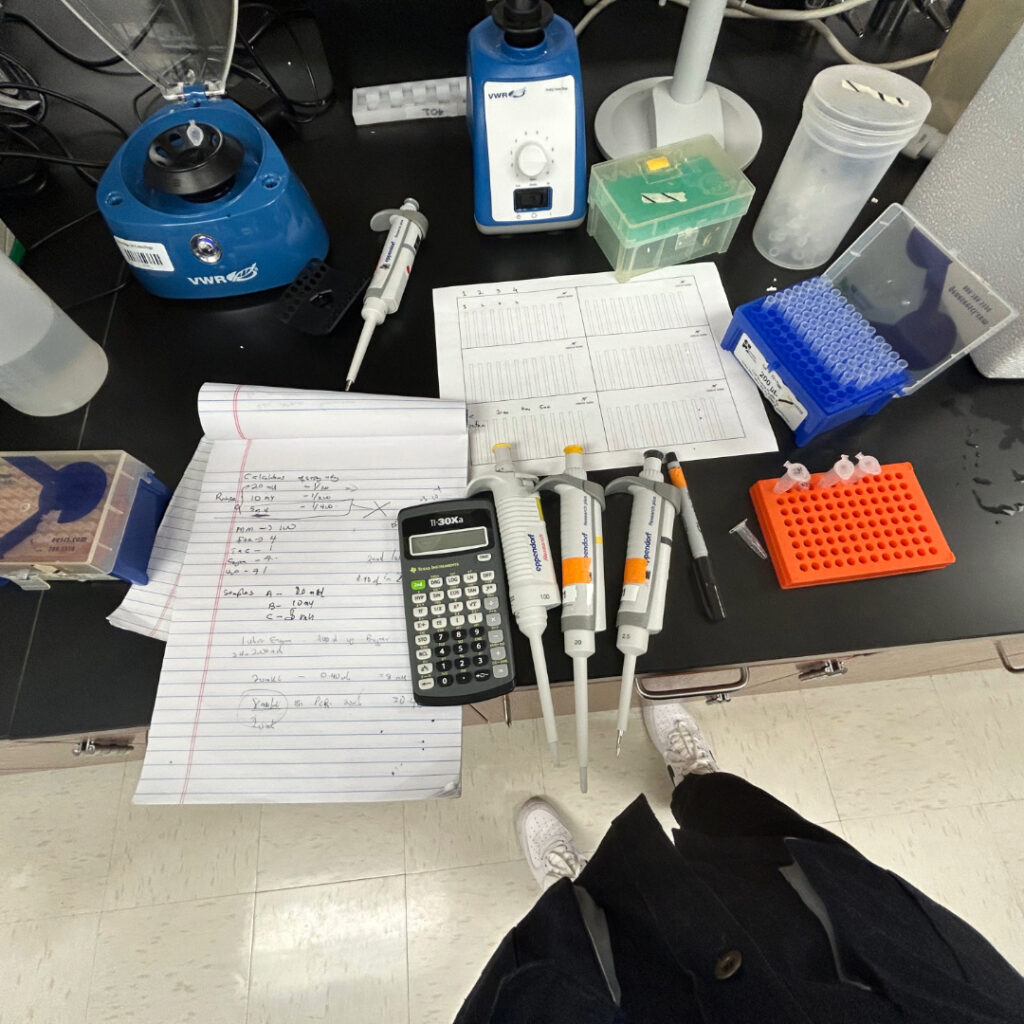

Collaboration with industry expert Mr. Williams from SeaD revealed the need for practical, simple, and cost-effective tools. The FSU research team developed a new PCR-lateral flow assay, making the process less expensive and more accessible to all domestic shrimpers and shrimp commodity boards.

“These assays are low-cost and species-specific, providing accurate results within two hours.”

The PCR Lateral Flow Assay involves taking very small tissue samples from seafood using a toothpick, followed by DNA extraction and amplification of a specific marker, which is used for species identification. These rapid, species-specific PCR-based tests eliminate the need for DNA barcoding and associated sequencing steps, drastically reducing the testing costs and time.

The research team focused on identifying white shrimp, which are frequently substituted with cheaper imported varieties. As they developed their tests, they recognized the need to account for various other shrimp species. Most recently, they devised a method for Pacific white shrimp, which is most commonly used to substitute domestic shrimp species. This test is currently being used by SeaD Consulting to test for imported shrimp.

The lab’s mission was to ensure the safety of seafood distributed nationwide. There are several risks associated with mislabeled seafood, including foodborne illnesses and economic fraud.

Samuel Kwawukume

Equipment used for conducting PCR lateral-flow assays test. Photo by Samuel Kwawukume.

Dangers of Seafood Fraud

In addition to shrimp, Dr. Singh’s Lab has developed tests for red snapper, which is frequently mislabeled. When fish are sold in processed forms, like filets, it becomes difficult to distinguish between them. Common substitutes for red snapper in the U.S. include cheaper options like tilefish or other cheaper options imported from other countries and sold under the generic name “snapper”. They can contain high levels of mercury and can pose significant health risks.

Some species used for substitution could be from Illegal, Unregulated, and Unreported (IUU) fisheries sources, which hurt seafood sustainability and are an environmental threat to ocean resources.

Each fish species carries unique toxins and parasites, making substitutions particularly dangerous. Mislabeled seafood can lead to foodborne illnesses. For instance, substituting red snapper with tilapia can expose consumers to parasites common in farmed freshwater fish. Swapping red snapper for improperly stored scombroid fish, like mahi-mahi, can result in toxic histamine levels and food poisoning.

Consumers cannot rely solely on packaging for authenticity. While some may believe they can detect seafood quality by taste, Dr. Singh and his lab emphasize that accurately identifying seafood species by taste is quite challenging. This issue not only threatens public health but also leads to economic fraud, as less expensive species are often substituted for more costly ones.

Implementing Seafood Traceability in the Industry

Regulatory agencies are increasingly adopting these innovative tools to ensure food safety and authenticity. An example comes from Williams and his team at SeaD, who used the tests developed by Kwawukume and the FSU team at the Louisiana Seafood Festival. This event highlighted a powerful tool that not only addresses regional specifics but also enhances accuracy in seafood identification.

Unfortunately, some vendors were found selling non-domestic shrimp while claiming they were locally caught. This incident underscores a larger issue: the fraudulent mislabeling of seafood, particularly Gulf shrimp, significantly misrepresents local products and poses a serious threat to multi-generational shrimping businesses.

“The repercussions of seafood fraud are dire for local communities, such as Dulac, Louisiana, where seafood fraud has economically devastated generations of shrimpers,” says Williams. “This situation highlighted the necessity for rebuilding seafood processing technology and infrastructure, as well as rapid genetic testing to combat mislabeling.”

Beyond Louisiana, many states along the Gulf, including Florida are impacted by seafood fraud. Florida consumers have a strong preference for seafood species like shrimp and red snapper, which are integral to the state’s culinary identity. However, the introduction of substitute species threatens both the authenticity of Florida’s seafood offerings and the seafood communities. Once these seafood communities and supporting infrastructure are gone, it will be a big loss to the country.

“The rising seafood costs underscore the need for effective regulation to ensure product integrity. By employing rapid testing methods at ports of entry, regulators can quickly identify and address mislabeled seafood, protecting consumers and supporting local businesses,” says Kwawukume.