Zeke Tuszynski is a master’s student in the Biological Sciences Department at Florida Atlantic University. Zeke was awarded a Guy Harvey Scholarship in 2023.

Since humans first began living near the ocean, sharks have left a potent impression on our collective minds. Over the millennia, they have inspired feelings ranging from fear to reverence. I have seen these animals many times on scuba and boating trips; each encounter has filled me with a sense of wonder. I grew fascinated by the vast oceanic voyages many of these animals make. Determined to learn more, I took my first steps into marine biology.

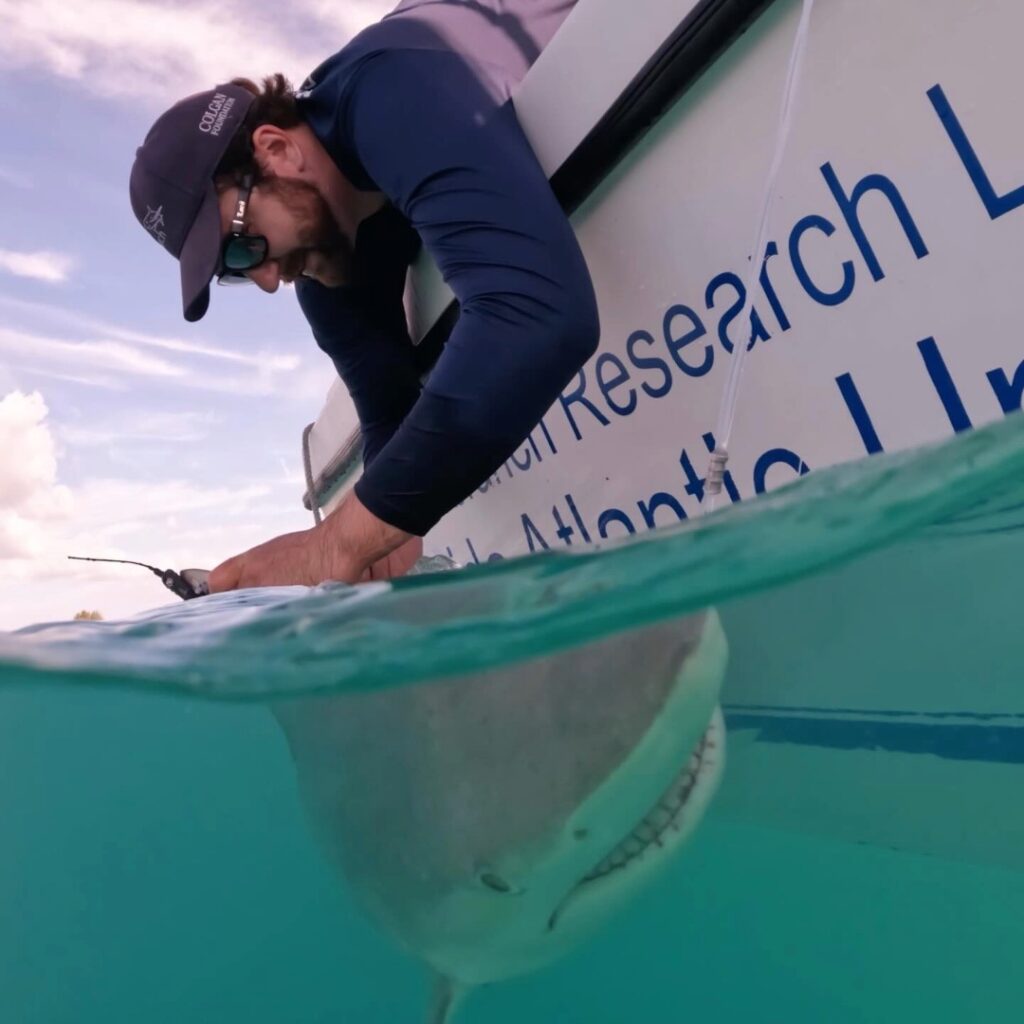

Zeke Tuszynski deploying a satellite tag on a captured blacktip shark. Image by Dr. Stephen Kajiura.

During my undergraduate studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, I had the opportunity to work with a NOAA research team at the NWFSC Maine Field Station. We used echosounders, a technology that can detect fish underwater using sound waves, to map the changing distribution of fish in Maine’s Penobscot River Estuary. After obtaining my bachelor’s, I interned at Stanford’s Hopkins Marine Starion where I got to care for captive tunas. It was here that I also learned the programming skills scientists use to track animals such as sharks.

Joining the master’s program at Florida Atlantic University has brought me closer to these animals than ever before. While working in Dr. Stephen Kajiura’s lab, I came face to face with 11 different shark species. Among the most memorable encounters were several large great hammerheads and a massive female tiger shark.

It was also here that I began my thesis research on the blacktip shark. Each year, these fish gather off the South Florida coast in thousands. They remain here from January through March. As April approaches, they migrate towards Georgia and the Carolinas where they spend their summer. While we know where these sharks travel, less is known about how the environment influences this migration. I am curious about how far offshore these animals travel. I also want to know what seasonal changes drive this migration each year.

To gather data on Florida’s coastal sharks, my lab mates and I look for them off the coast of Palm Beach. It was certainly not the research site I had envisioned: we fish for sharks with mansions and luxury condominiums as a backdrop. The animals we seek can be found mere yards away from the pristine white beaches. We catch these animals on drumline fishing gear, which consists of a line attached to a concrete weight, a marker buoy, and a baited circle hook. Once hooked, sharks are hauled next to the boat by hand, which is no easy task if you have a 10-foot tiger shark on the line! We record each animal’s species, length, and sex. We also attach a small plastic identification tag to the animal before release. Should the shark be captured again, this tag will let us know how far the animal traveled.

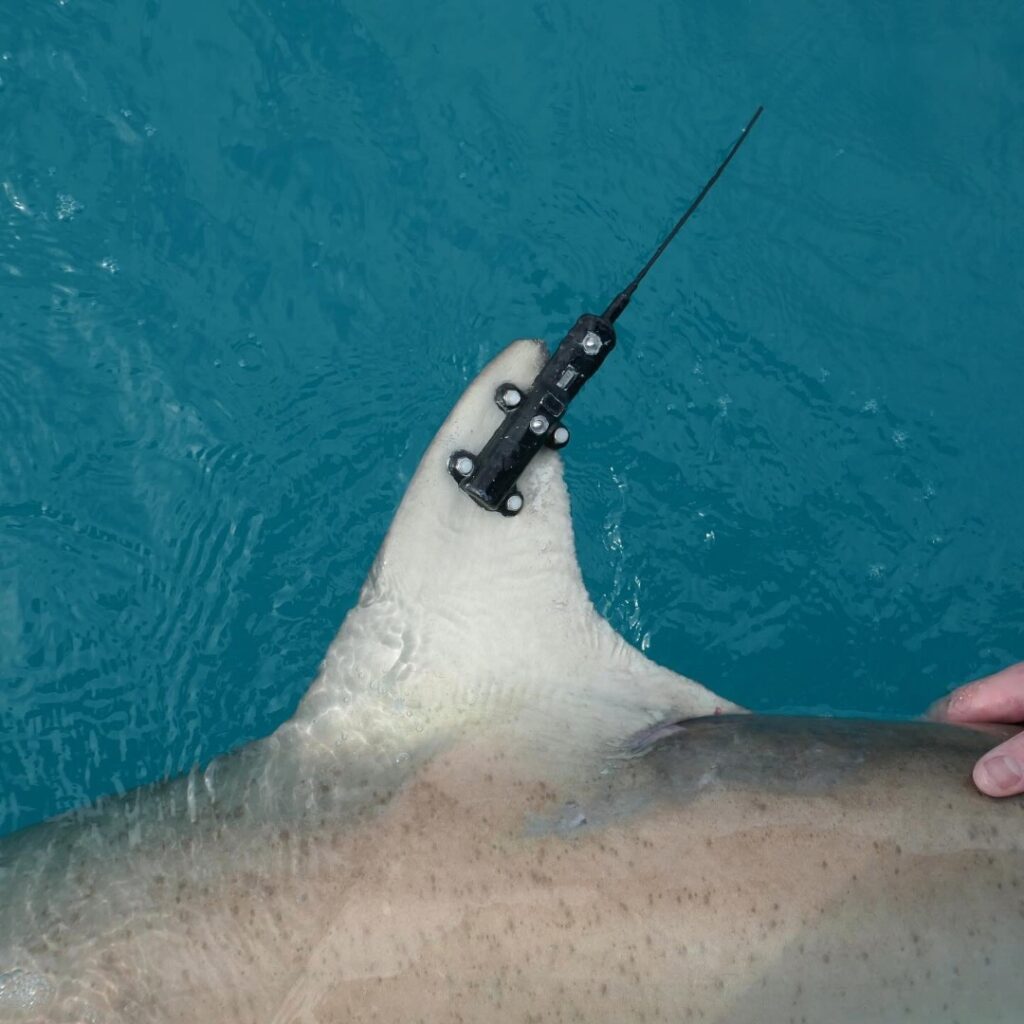

Blacktip sharks also receive a satellite tag, which attaches to the animal’s dorsal fin. Every time the fin breaks the surface, the tag’s onboard transmitter will communicate with an array of satellites, giving us the shark’s location. The tag also contains sensors that tell us what percentage of the time the shark spent in waters of different temperatures. The tag will transmit until the onboard battery runs dry and the nuts holding it in place rust off, allowing the shark to discard the device.

As predators, blacktips sharks play a vital role in balancing our coastal ecosystems. A change in their migration patterns may have dire environmental consequences.

Zeke Tuszynski

Detail of fin-mounted tag and hardware. Image by Dr. Stephen Kajiura.

Once I receive data from the satellites, I can then map the locations of tagged sharks using software called ArcGIS and compare them with data on environmental features such as temperature and seafloor depth.

To date, we have found that these sharks range from the beach to more than 43 miles offshore. The vast majority were detected over the continental shelf, a section of relatively shallow ocean that extends along the coast. I also found that these sharks spend most of their time in waters between 71° F and 78 °F. Blacktip sharks likely leave Florida in the spring when rising water temperatures exceed this thermal preference range.

With these findings in mind, my lab has noticed a disturbing trend. Since we started surveying these sharks in 2011, we have seen fewer and fewer blacktips here each winter. We are also detecting animals as far north as New York. It could be that climate change is pushing the range of these animals north.

Now, why should humans be concerned about this? As predators, blacktip sharks play a vital role in balancing our coastal ecosystems. A change in their migration patterns may have dire environmental consequences.

Like many shark species, blacktips are threatened by overfishing and accidental capture or bycatch. Understanding where and why these animals migrate is vital information for managing their fisheries.

It has truly been a blessing to work this closely with these awe-inspiring animals. By understanding why these sharks undertake these vast journeys, I am to provide information that fisheries management organizations can use to protect them. I also hope that sharing my findings on shark migration with the public can inspire the same appreciation for these animals that I have.